The Obama administration is working on a series of deals that

would, for the first time, allow foreign governments to serve U.S.

technology companies with warrants for email searches and

wiretaps—a hotly debated issue in global debates over privacy,

security, crime and terrorism. The administration is preparing to

announce its first such agreement with the United Kingdom.

Word of the plans came one day after a federal appeals court

ruled that Justice Department warrants couldn't be used to search

data held overseas by Microsoft Corp., dealing the agency a major

legal defeat.

Brad Wiegmann, a senior official at the agency, discussed the

efforts during a public discussion Friday.

The court's decision in favor of Microsoft could prove to be a

major barrier to the Obama administration's proposed new rules to

share data with other nations in criminal and terrorism probes,

which would be sharply at odds with the ruling. It might also lead

companies that provide services over the internet to reconfigure

their networks to route customer data away from the U.S., putting

the data out of the reach of federal investigators if the

administration's plan fails.

The Justice Department has indicated it is considering appealing

the ruling to the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, agency officials are pressing ahead with their own

plan for cross-border data searches.

Under the proposed deals described by Mr. Wiegmann, foreign

investigators would be able to serve a warrant directly on a U.S.

firm to see a suspect's stored emails or intercept their messages

in real time, as long as the surveillance didn't involve U.S.

citizens or residents.

"They wouldn't be going to the U.S. government, they'd be going

directly to the providers," said Mr. Wiegmann. Any such arrangement

would require that Congress pass new legislation, and lawmakers

have been slow to update electronic privacy laws.

U.S. officials are preparing to announce such an agreement with

U.K. authorities. The deal would need to be approved by the

legislatures of both countries before it could take effect.

That agreement could become a template for similar deals with

other countries, officials said.

Mr. Wiegmann said the U.S. would strike such deals only with

nations that have clear civil liberties protections to ensure that

the search orders aren't abused.

"These agreements will not be for everyone. There will be

countries that don't meet the standards," he said.

Greg Nojeim, a privacy advocate at the Center for Democracy and

Technology, criticized the plan. He said it would be "swapping out

the U.S. law for foreign law" and argued that U.K. search warrants

have less stringent judicial protections than U.S. law.

British diplomat Kevin Adams disputed that, saying the proposal

calls for careful judicial scrutiny of such warrants. Privacy

concerns over creating new legal authorities are overblown, he

added.

"What is really unprecedented is that law enforcement is not

able to access the data they need," Mr. Adams said. The ability to

monitor a suspect's communications in real time "is really an

absolutely vital tool to protect the public."

While Thursday's court decision represented a victory for

Microsoft, which strives to keep data physically nearby its

customers, it may not be a positive development for all internet

companies, said University of Kentucky law professor Andrew Woods.

Yahoo, Facebook and Google operate more centralized systems. They

didn't file briefs in support of Microsoft's position in the case,

he noted.

Mr. Woods warned that increased localization of data could have

the unintended consequence of encouraging governments to become

more intrusive.

"If you erect barriers needlessly to states getting data in

which they have a legitimate interest, you make this problem

worse," he said. "You increase the pressure that states feel to

introduce backdoors into encryption."

Microsoft President and Chief Legal Officer Brad Smith said the

company shares concerns about the "unintended consequences" of

excessive data localization requirements.

"But rather than worry about the problem, we should simply solve

it" through legislation, Mr. Smith said. Microsoft supports the

proposed International Communications Privacy Act. That legislation

would, among other provisions, create a framework for law

enforcement to obtain data from U.S. citizens, regardless of where

the person or data was located.

Thursday's ruling could lead some Microsoft rivals that offer

email, document storage, and other data storage services, but which

haven't designed systems to store data locally, to alter their

networks, said Michael Overly, a technology lawyer at Foley &

Lardner in Los Angeles.

Google, for example, stores user data across data centers around

the world, with attention on efficiency and security rather than

where the data is physically stored. A given email message, for

instance, may be stored in several data centers far from the user's

location, and an attachment to the message could be stored in

several other data centers. The locations of the message, the

attachment and copies of the files may change from day to day.

"[Internet companies] themselves can't tell where the data is

minute from minute because it's moving dynamically," Mr. Overly

said.

The ruling could encourage tech companies to redesign their

systems so that the data, as it courses through networks, never

hits America servers.

A person familiar with Google's networks said that such a move

wouldn't be easy for the company.

Jack Nicas contributed to this article.

Write to Devlin Barrett at devlin.barrett@wsj.com and Jay Greene

at Jay.Greene@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 15, 2016 18:25 ET (22:25 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

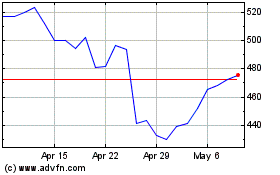

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024