By Ryan Tracy and Leslie Scism

WASHINGTON -- A judge invoked broad legal grounds to rescind

federal oversight of MetLife Inc., calling into question the

process the Obama administration has used to bring other large

insurers under the Federal Reserve's thumb.

U.S. District Judge Rosemary Collyer, who last week overturned

regulators' determination that distress at MetLife could put the

economy at risk, Thursday unsealed her written opinion in the case.

She took regulators to task for an "unreasonable" decision that

didn't consider potential costs and relied on a process that was

"fatally flawed."

The administration is expected to appeal the ruling in the

coming weeks, but hasn't said explicitly that it will do so. One

administration official said Thursday he believes an appeal is

likely.

"We intend to continue defending vigorously the process and the

integrity of [the Financial Stability Oversight Council's] work,

and I am confident that we will prevail," said U.S. Treasury

Secretary Jacob Lew, who heads the oversight council, in a

statement Thursday. "This decision leaves one of the largest and

most highly interconnected financial companies in the world subject

to even less oversight than before the financial crisis."

The findings by Judge Collyer amount to a broadside against one

of the core overhauls the Obama administration and Congress enacted

in response to the 2008 financial crisis, when financial

institutions that fell outside federal oversight put the economy at

risk. Her opinion contradicts some of the top federal financial

regulators and sets up a legal battle that will determine whether

they continue to supervise some of the largest U.S. insurance

companies.

In the 33-page document, Judge Collyer blasted the FSOC's

process for tagging MetLife as "systemically important financial

institutions" under the 2010 Dodd-Frank law, implicitly also

criticizing a similar process that was used to tag MetLife's two

biggest rivals -- American International Group Inc. and Prudential

Financial Inc. -- as SIFIs. The oversight council includes the

heads of the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission,

and other regulators.

AIG and Prudential declined to comment Thursday, but people

familiar with the matter have said the firms are expected to review

the MetLife case and consider their own legal challenges.

MetLife, which received the SIFI label by a 9-1 vote of the

council in December 2014, is the only firm to challenge regulators'

decision in court so far. But it is possible AIG and Prudential

could follow with their own lawsuits if MetLife is ultimately

successful, undoing one of the Obama administration's key

post-financial crisis regulatory accomplishments.

"We remain pleased with the U.S. District Court's decision," a

spokesman for MetLife said.

By faulting the oversight council's process rather than its

overall findings, Judge Collyer may have left the door open for the

group to redo its work and once again subject MetLife to federal

oversight.

"We believe the court has left the door open for the Financial

Stability Oversight Council to redesignate MetLife as a

systemically important financial institution, though the process

may be more time-consuming and complicated," Guggenheim Securities

analyst Jaret Seiberg wrote in a note to clients Thursday.

Mr. Seiberg also said that MetLife is undertaking a separate

initiative to shed some assets in a way that could make the company

appear less worrisome to regulators in the future.

Dodd-Frank gives regulators the authority to designate firms as

SIFIs if their failure or activities could threaten financial

stability. The SIFI label comes with tougher oversight from the

Fed, including annual stress tests and limits on borrowing that are

expected to go beyond those applied to other insurance companies,

which are primarily regulated by the states.

In designating MetLife, regulators outlined a range of risks

associated with the firm and described how, if the firm got in

trouble, stress could spread quickly to other parts of the

economy.

Judge Collyer said those findings included assumptions that

weren't backed up by analysis of potential losses at MetLife and

its counterparties.

"Every possible effect of MetLife's imminent insolvency was

summarily deemed grave enough to damage the economy," she

wrote.

Mr. Lew's statement said "the financial crisis showed direct and

predictable counterparty losses are not often the means by which

the failure of a financial company could destabilize markets and

threaten the U.S. economy."

The judge also faulted regulators for process fouls.

In April 2012, the council issued a final rule interpreting its

authority under Dodd Frank. She said that document made promises

that the oversight council later abandoned without explanation,

violating administrative law and rendering its decision arbitrary

and capricious. Specifically, she said the FSOC had promised to

assess MetLife's vulnerability to financial distress, but didn't do

so, and that it changed its definition of what it means to threaten

the financial stability of the U.S.

The oversight council has argued it didn't depart from its

initial promises and was required to assess only the impact of

MetLife's failure, not the likelihood of it.

Judge Collyer also invoked a June 2015 Supreme Court decision on

regulatory cost-benefit analysis, known as Michigan v.

Environmental Protection Agency. The decision, written by the late

Justice Antonin Scalia -- whose son Eugene is a partner at Gibson,

Dunn & Crutcher LLP representing MetLife -- found the EPA acted

unreasonably when it didn't consider cost in making a regulatory

decision.

"Because FSOC refused to consider costs as part of its calculus,

it is impossible to know whether its designation 'does

significantly more harm than good,'" Judge Collyer wrote, quoting

the Michigan decision.

Mr. Lew said Congress chose not to require the FSOC to conduct a

formal cost-benefit analysis "for good reasons" because doing so

would impair regulators' ability to address risk. He said crises

are difficult to predict, but their damage can be far-reaching.

University of Michigan law professor Michael Barr, who was an

architect of the Dodd-Frank law during a stint at the Treasury

Department, said he thinks the decision will be overturned on

appeal.

"I think the judge fundamentally misunderstands what the FSOC is

required to do.... I think the judge is wrong."

Write to Ryan Tracy at ryan.tracy@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 07, 2016 15:06 ET (19:06 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

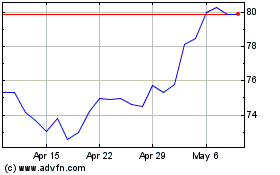

American (NYSE:AIG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

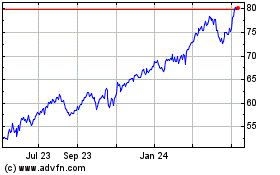

American (NYSE:AIG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024