(FROM THE WALL STREET JOURNAL 3/10/16)

By Christina Rexrode and Emily Glazer

The nation's largest banks paid fines totaling about $110

billion for their role in inflating a mortgage bubble that helped

cause the financial crisis. Where did that money go?

In New York, the annual state fair is using bank-settlement

money to build a new horse barn and stables. In Delaware, proceeds

are being used to subsidize email accounts for local police. In New

Jersey, a mortgage firm owned by a former reality-television star

collected $8.5 million as a reward for reporting a bank's

misconduct.

Banks also helped tens of thousands of homeowners with their

mortgages in neighborhoods from Jacksonville, Fla., to Riverside

County, Calif., funded loans for low-income borrowers and donated

to dozens of community groups and legal-aid organizations.

Yet some of the biggest chunks of money stayed with the entity

that levied the fines in the first place. Of $109.96 billion of

federal fines related to the housing crisis since 2010, roughly $50

billion ended up with the U.S. government with little disclosure of

what happened next, according to a Wall Street Journal

analysis.

The Journal reviewed the terms of more than 30 settlements,

filed public-records requests with a dozen agencies at the federal

and state level and spoke to dozens of homeowners and others who

obtained payouts, tried to or were otherwise involved with the

distribution of the settlements. The results represent the most

detailed breakdown yet of the billions paid out in the

unprecedented deals.

Out of the $110 billion, the Journal found that:

The Treasury Department received almost $49 billion of the

funds, including money the agency received directly and sums

funneled to it by other departments, including government-chartered

housing associations Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. How the money is

spent isn't specified.

About $45 billion was earmarked for "consumer relief," a

category that includes money dedicated to helping borrowers and

funding housing-related community groups.

The Justice Department, whose prosecutors led many of the

negotiations with banks, collected at least $447 million. How it

spends the money isn't specified.

States received more than $5.3 billion, usually to spend as they

saw fit. Almost all states received payments from a national

settlement in 2012 over mortgage-servicing abuses, and seven also

received payments in the Justice Department's blockbuster

mortgage-securities settlements that started in 2013.

Roughly $10 billion went to other recipients, including

housing-related federal agencies, two federal agencies responsible

for cleaning up failed banks or credit unions, and whistleblowers

who helped the Justice Department. Some funds from these deals

typically revert to the Treasury.

The White House said tens of billions of dollars have been

recovered for American consumers since 2009, including funds that

went to government agencies and programs and the Treasury,

according to Deputy White House Press Secretary Jen Friedman.

The lack of detailed disclosure bothers some people. "The

government has a responsibilityto its citizens to be transparent

about where its revenues are going," said Aaron Klein, who focuses

on financial regulation for the Bipartisan Policy Center in

Washington, D.C. "When settlement funds just go into the black box

of the general fund of the government, who is accountable?"

Bank executives grumble privately about the opaque process and

are critical the government didn't ensure more money went to

housing-related issues.

Given the historic scope of the fines, the money "shouldn't just

be a slush fund," said Francis Creighton, executive vice president

of government affairs at the Financial Services Roundtable, an

industry group.

The settlements arose from bank behavior prosecutors said fueled

the housing crisis and aggravated its effects. Among other things,

banks were accused of pushing expensive mortgages on unqualified

borrowers, selling hundreds of billions of dollars of securities

that they knew were likely toxic and filing fraudulent paperwork on

people being booted from their homes.

The Journal analysis included fines paid by the four biggest

U.S. banks -- Bank of America Corp., J.P. Morgan Chase & Co.,

Citigroup Inc. and Wells Fargo & Co. -- as well as investment

banks Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. One settlement,

the Justice Department's $16.65 billion deal with Bank of America,

was the biggest ever imposed by the U.S. government on a single

entity.

The analysis excluded settlements from private lawsuits --

including some investor suits that resulted in multibillion-dollar

payouts -- as well as fines levied on banks for conduct outside the

housing and mortgage crisis.

Fines generally are funneled to the Treasury, which manages the

federal government's finances. There, the money goes into the

government's general fund,where it can be spent on any budgeted

item, including employee salaries or reducing the deficit. The

Treasury Department said the settlement money isn't specifically

tracked.

A spokesman, Rob Runyan, said the funds are "spent as Congress

authorizes."

Most of the money attributed to Treasury in the analysis came

indirectly. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which buy loans from

lenders and package them into securities, and their regulator, the

Federal Housing Finance Agency, collected more than $34 billion in

fines. The bulk was transferred to Treasury, which spent $187.5

billion to bail out Fannie and Freddie during the financial

crisis.

The housing companies said they have been profitable since 2012

and have together paid the Treasury about $246 billion in

dividends.

There is precedent for broad use of penalties. Funds from a 1998

deal for tobacco companies to pay states an estimated $200 billion

over 25 years, intended to help states pay for smoking-related

health costs, have also been used to balance state budgets and to

fund school reading programs, after-school services and

infrastructure.

A Justice Department spokesman, Patrick Rodenbush, said the bank

settlements "hold financial institutions accountable for various

forms of fraud in the mortgage industry" and that the money

compensated "government agencies and programs harmed by the banks'

conduct."

In three major settlements analyzed by the Journal -- $13

billion from J.P. Morgan Chase, $7 billion from Citigroup and the

$16.65 billion from Bank of America -- banks were censured for

misleading investors about shoddy mortgage securities. The Justice

Department played the lead role in doling out pieces to other

agencies and states involved in the litigation, according to people

involved in the lawsuits.

Seven states, most with attorneys general who played important

roles in previous litigation against the banks, participated

directly in those settlements and received funds for special

projects and local residents.

In New York, Gov. Andrew Cuomo is using proceeds to help replace

the Tappan Zee Bridge north of New York City, renovate the Port of

Albany and provide high-speed Internet access in rural

communities.

Last year, when Mr. Cuomo announced in a speech that the New

York state fair would get $50 million for an overhaul, Troy

Waffner, the acting director of the fair, jumped up and down and

called his mother. The fair will use the funds for improvements

like a bigger concert stage, making the grounds more accessible to

the disabled and an equestrian facility with warm-water washing

stations for the horses.

Some New York housing advocates said more money should have been

directed to areas directly affected by the financial crisis. Mr.

Waffner is among those who support a broader distribution. "The

more money we can invest in bringing back the economy. . .I don't

think that's a bad use of funds," he said.

Gov. Cuomo's office said his own $20 billion, five-year

investment in affordable housing, homeless services and related

programs, "far exceeds what the state has collected from financial

settlements," said Morris Peters, a spokesman for Mr. Cuomo's

budget office.

Most states have directed settlement funds to state pension

plans, which oversee savings accounts for public employees such as

teachers, judges and other government workers. Many of those funds

had invested in mortgage securities that went sour during the

crisis. California sent the bulk of its $700 million in bank

penalties to its two biggest statepension funds. The office of

state Attorney General Kamala Harris said it held back $28 million

for itself "to support this and related litigation."

Out of the $110 billion in settlements, the Justice Department

retained at least $447 million, the Journal's analysis showed. The

department keeps up to 3% of most civil fines collected, in its

Three Percent Fund. It isn't required to disclose how much money it

puts in the fund or how it is spent.

Last year, a report by the Government Accountability Office, the

investigative arm of Congress, estimated the Three Percent Fund

collected $158 million from all eligible civil fines in fiscal

2013.

Diana Maurer, a GAO director, said her office believes the

Justice Department should develop better plans for the use of the

Three Percent Fund. The Justice Department countered, according to

Ms. Maurer, and said it wanted to avoid creating improper

incentives for prosecutors.

"They did not want to plan out" the spending for the long term,

Ms. Maurer said. "And we said, 'No, you really should, this is

hundreds of millions of dollars.' "

The Justice Department didn't comment on the use of the

fund.

Banks agreed to provide an estimated $45 billion from the

settlements in the form of consumer relief.

(MORE TO FOLLOW) Dow Jones Newswires

March 10, 2016 02:48 ET (07:48 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

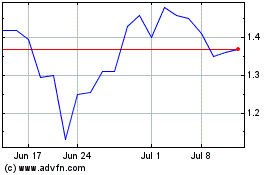

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

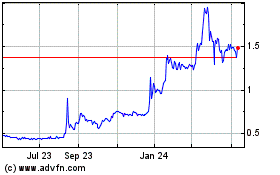

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024