By Doug Cameron and Jon Ostrower

Boeing Co. shares fell sharply Thursday as fresh concerns about

the company's accounting method for its jetliners added to investor

anxiety about the outlook for the commercial-aircraft market.

The world's largest aerospace company long has employed a system

called program accounting that averages out expected costs and

revenue on airplane programs over years of production, enabling it

to book anticipated future profits as part of current earnings.

The system is compliant with Generally Accepted Accounting

Principles but rarely used by other companies, and some investors

and shareholders have raised concerns that it builds long-term

assumptions into Boeing's financial reporting about factors that

are too uncertain.

Attention to the accounting method renewed on Thursday after a

report that the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating

whether Boeing properly accounted for the long-term costs and

expected sales of two of its most prominent jet programs--the 787

Dreamliner and the 747 aircraft. The report, by Bloomberg News,

which cited people with knowledge of the matter, said SEC

enforcement officials hadn't reached conclusions and could decide

against bringing a case.

Boeing and the SEC declined to comment. "We typically do not

comment on media inquiries of this nature," said John Dern, a

Boeing spokesman.

Boeing shares ended down 6.8% in Thursday trading--after

recovering from much steeper declines--to their lowest closing

price since September 2013. The stock is down 25% this year on

concerns that years of record jet deliveries may be petering out

due to strong competition and global economic weakness.

Boeing declined Thursday to comment on its accounting methods.

In the past, Boeing has said that program accounting, which it has

used for decades, is critical to avoiding big swings in earnings

that could make it difficult to pursue projects that can stretch

over years but require huge outlays up front.

Several analysts on Thursday called the stock selloff overblown,

saying that even if Boeing had to change its accounting practices

the likely impact on its cash flow would be small.

However, accounting method aside, if Boeing's cost-saving

projections fall short, then it won't meet cash-generation goals,

eagerly awaited by investors.

Program accounting requires Boeing to estimate cost levels,

sales volumes, and anticipated productivity improvements and

pricing for jets that might be made years in the future. Some

analysts and investors have said that the difficulty of predicting

such long-term factors could make such accounting conclusions

arbitrary.

From the Dreamliner's start, Boeing has had to spend more

producing each of the technologically advanced,fuel-efficient jets

than it gets selling them. Boeing tallies the accumulated shortfall

as "deferred production costs."

For the Dreamliner, that tally grew to $28.5 billion as of the

fourth quarter after delivery of more than 350 of the aircraft

since 2011.

Boeing expects to erase that deficit over time because costs for

making jets generally drop as manufacturers scale up output and

learn to produce more efficiently. The company said last month that

it expects to start making money on a unit basis on each 787

delivery later this year.

Those record costs mean Boeing must average $30.4 million in

profit per plane on its outstanding order backlog, all before it

expects to recover another $8.7 billion on 158 jets it hasn't yet

sold, according to its SEC filings.

Some analysts are concerned that the pace of cost reduction has

fallen short. Boeing's cost-cutting to date is more in line with

its recent jetliner programs, such as its 777, not a more

aggressive decline required to recover its costs, said UBS analyst

David Strauss.

Credit Suisse analyst Rob Spingarn in a December investor note

wrote that Boeing "may be overly optimistic" about its ability to

recover all of its deferred costs, potentially falling short by an

estimated $7.5 billion over its next nearly 1,000 deliveries.

Boeing in 2002 paid $92.5 million to settle a class-action suit

alleging it manipulated program accounting on the 777 jet to shield

the timing of cost overruns and production problems five years

earlier, according to court documents. The company didn't admit

wrongdoing.

Jeff Wilks, director of the School of Accountancy at Brigham

Young University, said program accounting "was trying to recognize

how perverse that reporting would be" if the huge initial costs of

production were reflected in a company's earnings. The risk, he

said, could come if a company "didn't foreshadow or give a good

sense of its expectations" for what it costs and revenues would

be.

Few other companies use program accounting. Rival Airbus

accounts for its jet programs differently, using International

Financial Reporting Standards, booking cost overruns as they occur

rather than trying to amortize them over the life of future

aircraft production.

Airbus took repeated hits to earnings during the development of

the A380 superjumbo as the plane's development and production costs

grew. Airbus last year began delivering the first A380 jets that no

longer lose money.

Boeing has adjusted its expectations for the Dreamliner several

times. It initially set the accounting block--the number of planes

over which it averages costs and revenue--at 1,100 aircraft,

already far larger than it has for earlier programs. It raised that

in 2013 to 1,300 aircraft when it announced plans to boost output,

amounting to about a decade of planned production. Boeing said

those estimates were driven by forecast demand for the jet.

The gap between accounting methods can be sizable. Boeing says

that earnings from operations in its commercial airplanes segment

last year would have been $2.67 billion on a unit-cost accounting

basis, compared with the $5.16 billion it reported using program

accounting.

In 2014, unit accounting would have created a $122 million loss,

compared with the $6.41 billion operating profit Boeing

reported.

Robert Wall and Aruna Viswanatha contributed to this

article.

Write to Doug Cameron at doug.cameron@wsj.com and Jon Ostrower

at jon.ostrower@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 11, 2016 19:49 ET (00:49 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

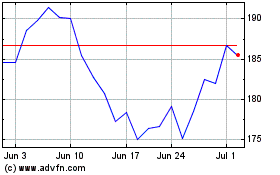

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024