Google Defends U.K. Tax Settlement Before Lawmakers

February 11 2016 - 7:50AM

Dow Jones News

Executives for Alphabet Inc.'s Google business defended their

settlement with the U.K.'s tax authority before a panel of British

lawmakers Thursday, trying to stanch criticism of a deal that

critics say let the search giant off too lightly.

In testy exchanges with lawmakers, Tom Hutchinson, Google's vice

president of finance, said the deal reached with the U.K.'s tax

authority was the largest settlement the Internet giant has paid

outside the U.S. He was appearing before parliament's public

accounts committee, which is tasked with ensuring British taxpayers

get value for money from the government.

The deal, in which Google agreed to pay £ 130 million ($189

million) in back taxes and boost future tax payments, sparked

outcry in the U.K. among those who say the Mountain View, Calif.,

company should have paid more. The U.K. is Google's second-largest

market after the U.S., with $7.07 billion in revenue from U.K.

clients in 2015.

Mr. Hutchinson defended the company's tax arrangements, saying

they comply fully with U.K. laws.

"We are paying the right amount of taxes," Mr. Hutchinson

said.

Also at the hearing, Matt Brittin, head of operations for Google

in Europe, the Middle East and Africa, said the Internet giant's

U.K. tax payments accurately reflected the economic activity the

company carries out in Britain.

"We are paying tax at 20% on our activities in the U.K.," Mr.

Brittin said, referring to the U.K.'s corporate-tax rate.

Google's defense of its deal is part of a broader effort by big

multinational to set templates for how they should cope with a

coming shake-up of global tax rules. Governments, particularly in

Europe, are changing international tax treaties and laws to force

companies like Google to pay more in taxes. Companies are now

moving to alter their structures to comply with new rules -- but

ideally without causing too much of a dent to the bottom line.

Amazon.com Inc., for instance, restructured its European

operations last year to start collecting revenue directly in

countries where its clients make purchases, shifting its tax base

away from its European headquarters in Luxembourg to countries like

the U.K. and France. But it isn't yet clear how much more—if

anything—the thin-margin Amazon retail business will end up paying

the taxman.

Google is also currently facing audits in multiple countries

including Italy and France, which is asking for as much as €1

billion ($1.13 billion) in back taxes and penalties. France's

economy minister said last month that Google was in talks with

France to settle that deal, but it isn't clear if a deal is

near.

At issue is how much business Google actually conducts in

individual European countries. The company employs thousands of

people across Europe as engineers or as marketers. But the company

argues that clients in countries like the U.K. and France don't

actually close any advertising deals with Google employees in those

countries; instead, clients buy all their advertising from the

local units' Irish parent. Local units like those in the U.K. make

all their revenue in fees paid by Google parents in Ireland and the

U.S.

Such arrangements, while legal, have attracted public ire and

political criticism. Stewart Jackson, a member of Prime Minister

David Cameron's ruling Conservative Party who sits on the public

accounts committee, accused Google's executives Thursday of using

these and other corporate structures to limit the company's tax

bill.

"You've made a choice to avoid tax, and have set up structures

specifically so to do," Mr. Jackson said, a charge Google's

executives denied.

Lawmakers on the panel repeatedly underlined public anger at

Google's tax arrangements in frequently hostile questioning.

"Our constituents are very angry. They live in a different world

to the world you live in," Meg Hillier, the committee's chairwoman,

told Mr. Brittin.

Under Google's U.K. deal, the company has committed to boosting

what the company pays its U.K. unit by an unspecified percentage to

reflect revenue from U.K. clients. For the 18 month period ended

June 30, Google says that it is paying an additional £ 13.8 million

in tax because of the settlement, out of total corporate tax for

the period of £ 46.2 million, according to the company's most

recent U.K. company filing.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a

group of rich countries, last fall issued a series of

recommendations aimed at stopping large companies in many

industries from using complex but legal structures to avoid paying

hundreds of billions of dollars in corporate income taxes every

year.

The European Union also proposed last month a common standard

intended to thwart tax avoidance schemes by multinationals. The

European Parliamentary Research Service estimates that corporate

tax avoidance results in a loss of tax revenue to the EU of about

€50 billion to €70 billion each year.

Write to Jason Douglas at jason.douglas@wsj.com and Sam

Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 11, 2016 07:35 ET (12:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

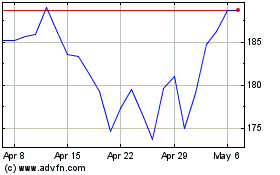

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

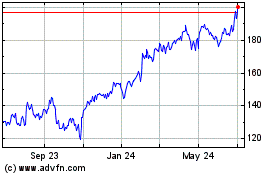

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024