By Denise Roland and Noemie Bisserbe

The history of inhalable insulins for diabetes care is full of

disappointments, but Sanofi SA thought a new approach would turn

all of that around. It was wrong.

The French drugmaker last month ended a licensing pact with

MannKind Corp. for the rights to sell the insulin inhaler Afrezza,

saying that despite substantial marketing efforts, the product was

unlikely to reach even the lowest patient levels anticipated. The

product, launched in the U.S. in February last year, notched just

EUR7 million ($7.8 million) in sales in 2015, as safety concerns

and reimbursement issues damped uptake.

Sanofi's bet on inhaled insulin shows the strain pharmaceutical

chiefs are under to acquire innovative products when their own

pipelines aren't delivering. It came at a tough time for the

company's all-important diabetes franchise, which has been forced

to offer deeper discounts on its products amid pricing pressure

from U.S. payers.

On Tuesday, Sanofi said sales of its diabetes drugs in the U.S.

slumped 25% at constant exchange rates to EUR1.1 billion in the

fourth quarter, dragging world-wide revenue from the diabetes

franchise down 13% to EUR1.9 billion. That weighed on total sales,

which came in at EUR9.3 billion, a drop of 1.6% on a constant

currency basis; including currency effects, revenue rose 2.3%.

Profit slid 75% to EUR334 million, while business net income,

which excludes certain one-time items, fell 7% to EUR1.7

billion.

Sanofi Chief Executive Olivier Brandicourt had been down the

inhaled-insulin path before. Nearly 10 years ago, he presided over

the multibillion-dollar flop of insulin inhaler Exubera as head of

metabolic and cardiovascular medicine at Pfizer Inc. Shortly after,

Novo Nordisk A/S and Eli Lilly & Co. shelved advanced plans to

develop their own inhaled products.

The failure of Exubera was, in large part, one of design:

diabetes patients were reluctant to use the unwieldy device in

public as it resembled a bong for smoking marijuana.

But others saw more fundamental reasons to scrap the idea: Novo

Nordisk said at the time that it couldn't overcome the fact that

inhaled insulin wouldn't eliminate the need for injections. That is

because only short-acting insulin, which is taken as a boost at

mealtimes, could be administered via an inhaler. Most diabetes

patients on insulin--those with Type 1 or advanced Type 2--also

take a long-acting version to provide a constant minimum level,

which would need to be injected.

Furthermore, doctors are cautious about prescribing inhaled

insulin because of worries it could lead to lung cancer in the long

term, said Simon O'Neill, director of health intelligence at

Diabetes UK, a nonprofit patient-advocacy group. While there is no

evidence that inhaled insulin causes lung cancer, other so-called

growth hormones have been linked to the disease.

Despite the industrywide retreat from inhaled insulin, former

Sanofi CEO Christopher Viehbacher believed the advantages of

inhaled insulin--speedier delivery to the bloodstream and a reduced

dependence on needles--meant it was still worth a bet. In 2014, he

agreed to pay MannKind up to $925 million, mostly in milestone

payments, for the rights to market the recently approved Afrezza.

By ending the agreement when it did, Sanofi capped its 2015 losses

at roughly EUR200 million, according to the company.

Analysts have predicted that without the support of Sanofi,

MannKind would end up in bankruptcy. Nonetheless, the Valencia,

Calif., company's new CEO, Matthew Pfeffer, has vowed it is "here

to stay." After the break with Sanofi, he told investors he planned

to cut the price of Afrezza and find a new partner for the product,

adding that MannKind had enough cash to get "comfortably into the

second half of the year."

MannKind also announced Jan. 22 that a newly established company

called Receptor Life Sciences had agreed to license MannKind's

inhaler technology in other diseases such as chronic pain and

neurologic diseases, paying $102 million in milestone payments but

no upfront cash.

One reason Sanofi believed it could succeed where Pfizer had

failed was that Afrezza's compact, whistle-shaped design overcame

Exubera's design flaws. A spokeswoman for Sanofi said the track

record of MannKind's founder, the billionaire Alfred Mann, also

bolstered the company's confidence in the product. Among Mr. Mann's

past ventures is the best-selling MiniMed insulin pump, now

marketed by Medtronic Inc.

But Sanofi badly underestimated the toll that safety concerns

would have on Afrezza's sales.

Existing worries among doctors over links with lung cancer were

compounded by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's warning that

inhaled insulin could cause breathing difficulties in people with

respiratory problems. The agency also required MannKind to run a

follow-on trial to determine whether Afrezza did increase patients'

cancer risk.

The agency also stipulated that doctors test patients' lung

health with a device known as a spirometer before prescribing the

drug. As most diabetes doctors don't have a spirometer, they would

need to send patients to another physician for the test.

Doctors might have been more willing to take on the risk and

effort of prescribing Afrezza if MannKind had demonstrated that it

is more effective than injected insulin, said Jane Chiang, senior

vice president for medical affairs at the American Diabetes

Association. But the company's clinical trials for Afrezza proved

only that it is as effective as, not better than, the injected

alternative, a status that is reflected in Afrezza's FDA label.

Further, most payers in the U.S. have Afrezza in a "tier three"

reimbursement category. That generally comes with higher copays and

requires physicians to explain why they prescribed Afrezza over

standard injected insulin. Sanofi also priced Afrezza at a premium

to its injectable counterparts.

MannKind's Mr. Pfeffer said pricing and reimbursement issues

"dramatically outweigh the other factors" related to Afrezza's slow

uptake.

Without a clinical trial showing that Afrezza worked better than

injected insulin, Sanofi's advertising campaign centered on the

novelty of inhaling versus injecting. But the company overestimated

the extent to which patients would switch to Afrezza due to a

needle aversion, said Eamonn O'Connor, an analyst at the

health-care consulting firm Decision Resources Group.

Despite these setbacks, Afrezza has gained a small but avid

following among patients who say it works significantly better for

them than injected insulin.

Forty-year-old Mike Parise said his blood sugar starts falling

within five to 10 minutes after he takes Afrezza, much quicker than

with injected insulin. "For someone who's had Type 1 for 20 years,

that's a beautiful thing," he said.

Jackie Klass, 52, said using Afrezza had helped her gain control

over her blood-sugar levels for the first time since she was

diagnosed 17 years ago and had "changed my life." She owns shares

in MannKind.

But many others didn't stick with it: A Sanofi spokeswoman said

that of the 6,000 patients prescribed Afrezza since its launch,

only 35% stayed on the treatment.

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com and Noemie

Bisserbe at noemie.bisserbe@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 09, 2016 16:21 ET (21:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

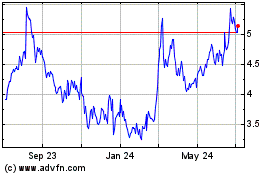

MannKind (NASDAQ:MNKD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

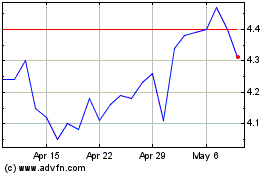

MannKind (NASDAQ:MNKD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024